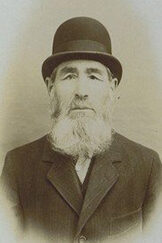

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman - The Vilna Gaon 1720-1797

Perhaps no other famous Jew is more closely linked to a specific city than the Vilna Gaon (the Genius of Vilna). Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, to give his rarely used full name, helped make Vilna (modern-day Vilnius) a world center for Talmudic learning. He was seen by many as the quintessential example of the “Litvaker Jew” – Orthodox Lithuanians dedicated to the rational, rigorous study of the Talmud and the punctilious observance of religious law.

The son of a renowned Talmudic scholar, his reputation as an intellectual genius began early. At age seven, he gave his first public discussion on the Torah. He studied alone from age 10, as his knowledge had outstripped the prominent rabbis hired to tutor him. Blessed with a photographic memory, he committed the entire Talmud to memory and was a self-taught expert in mathematics, astronomy, and Hebrew grammar. Throughout his life, he argued that knowledge of secular and scientific subjects was critical to a full understanding of the Talmud.

The Gaon was also known for his piety, reclusive personality, and ascetic lifestyle. He married at 18 but spent the next years wandering Eastern Europe alone, living off charity while collecting rare Jewish manuscripts that would later make up his extensive personal library. He returned to Vilna in 1748, where he would remain for the rest of his life (apart from a brief, abandoned attempt to travel to the land of Israel). Refusing any official position, and sleeping only two hours a night, he devoted himself to study and was rarely seen in public apart from occasional lectures to a few select students.

Nonetheless, his influence was vast. His follower Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin established a famed yeshiva that carried out the Gaon’s approach and which became a model for subsequent Talmudic education in Eastern Europe. The Gaon’s extensive writings, predominantly commentaries on classic Jewish texts, are still studied by many Orthodox Jews today due to their innovative approach, range, and erudition.

He is also famous as a leader of the so-called Mitnagdim, the opponents of the mystical Hasidic movement that spread rapidly during his lifetime. While personally steeped in Kabbalistic and mystical ideas, the Gaon feared that this new populist movement could damage traditional religious observance and customs and encourage support of false messiahs. He banned pious Jews from marrying into Hasidic families and excommunicated Hasidic leaders. The Mitnagdim-Hasidic hostility gradually faded but the Vilna Gaon’s reputation as a giant of Jewish religious life remains.

Rabbi Israel Salanter 1808-1883

Rabbi Israel Salanter, the father of the Musar (Morality) movement, helped transform the spiritual focus of Lithuanian Jewry in the 19th century. The son of a rabbi, Salanter was an outstanding Talmudic scholar and Orthodox leader. Nonetheless, he shocked many in the traditional yeshiva world by arguing that Talmudic learning and observance of religious laws needed to be supplemented by intense self-introspection and a commitment to ethical behavior.

Married by the age of 14, he was still a young man when in 1842 he was appointed head of a major yeshiva (religious seminary) in Vilna. Upset by criticism that he had superseded older rabbis, he left to open a new yeshiva and began to attract followers drawn by his reputation for righteousness and his innovative approach. When cholera spread through Vilna in 1848, he called on Jews not to fast during Yom Kippur, even eating and drinking himself while leading his synagogue in prayer.

In 1848, he moved to Kovno (Kaunas) where his inventiveness included opening a school for Musar (ethical and moral) studies alongside but separate from the traditional house of Torah learning. He was unusually active in outreach efforts – teaching businessmen and traders rather than just yeshiva students – and stressed that Musar could make traditional Judaism more relevant to Jews drawn by reform and secularist ideas. Some have argued that Salanter’s teachings about the role of the subconscious and his belief that moral ideas from the Torah can be internalized through repeated recitation of certain passages anticipated Freudian and behaviorist theories.

Prone to depression, Salanter left Lithuania in 1857 to recover in Germany. Unusually for an Eastern European rabbi, he spent his last decades trying to strengthen religious attitudes in Western Europe. He also embarked on the first attempt to translate the Talmud into a secular language – German. Nonetheless, his most direct influence was on changing the nature of Jewish religious education especially in Lithuania. After his death, the Musar movement spread through its yeshivas. Musar took on various and sometimes extreme forms, such as yeshiva students trying to overcome their sense of pride through subjecting themselves to public humiliation. In more recent times, there has been a revival and reinterpretation of Musar including among non-Orthodox communities.

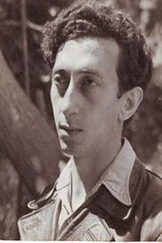

Chaim Grade 1910-1982

One of the great Yiddish writers of the 20th century, Chaim Grade was born in Vilna, the city about which he would write superbly. His parents’ diverse ideologies – his Hebrew-teacher father was an outspoken advocate of the Jewish enlightenment and often clashed with Vilna’s rabbinical establishment, while his mother was a devout woman who sold fruit to help the family eke out a living – influenced his writing, which often dealt with the tension between religious faith and skepticism.

Grade was educated in some of the most religiously extreme institutions of Lithuanian Jewry. From the age of 13, he studied at the Novaredok Musar Yeshiva – where students would deliberately humiliate themselves in order to break their attachments to personal desires – before becoming a chosen student of the Chazan Ish, one of the most influential ultra-Orthodox rabbis of the 20th century.

However, at age 22, Grade abandoned religious life and became a secular poet and writer. Associated with the Yung-Vilne (Young Vilna) literary group, his breakthrough volume of poetry Yo (Yes) dealt with his escape from religious coercion. His 1939 epic poem Musernikes (Moralists) explored the spiritually tormented lives of students at the Novaredok Yeshiva, striving for religious and ethical perfection but riven with lusts and self-doubts.

When the Nazis invaded Lithuania in 1941, Grade fled to the Soviet Union. His wife and daughter remained in Vilna and were killed. Many of his subsequent poems would deal with that loss and are considered key early examples of Holocaust literature. In 1948, Grade immigrated to the US where, alongside poetry, he wrote novels and short stories that realistically, unsentimentally, depicted the lost Jewish world of Vilna, from its great rabbis and their petty vanities to everyday people and their often extraordinary lives.

When he died in 1982, he was lionized in Yiddish literary circles but was largely unknown to English readers. However, the posthumous translations of his memoir My Mother’s Sabbath Days and his novel The Yeshiva led to new interest in Grade. He is now considered by many to be the equal of his more famous counterpart in Yiddish literature, the Nobe Laureate, Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Abba Kovner 1918-1987

Abba Kovner, partisan and poet, was born in Sevastopol, a Crimean port, before moving to Vilna (Vilnius) as a child. A “born leader,” Kovner graduated from a Hebrew academy and was active in Hashomer Hatzair, the socialist-Zionist youth group that helped shape his overpowering sense of commitment and willingness to sacrifice himself for a greater Jewish cause. Refusing opportunities to escape to Palestine, Kovner was in Vilna when it was occupied by Nazi Germany in June 1941. Within a matter of months, this famous Jewish community had been devasted with over two-thirds of its population killed by Nazis and Lithuanian collaborators. Kovner survived by hiding in a convent. Throughout his life he would refer to the nun who sheltered him and others as Ima, or mother.

In December 1941, Kovner slipped back into the ghetto where the remaining Jews of Vilna lived in appalling conditions and under Nazi control. He helped bring together the ghetto’s divided Jewish political factions into the United Partisan Organization (or FPO). This group trained fighters, gathered weapons, and prepared for what they accepted would be a doomed uprising against the Germans. To galvanize support, Kovner wrote a manifesto that was perhaps the first time that a Jew publicly warned that Hitler intended to murder all of Europe’s Jews. He called on Jews, faced with overwhelming odds, not to “go like lambs to the slaughter” but instead to fight to the end. “True, we are weak and helpless, but the only answer is resistance. Brothers! Better to fall as free fighters than live at our murderers’ mercy.”

While this manifesto inspired Jewish resistance efforts throughout Eastern Europe, the Vilna ghetto rejected Kovner’s pleas for a mass uprising. When the ghetto was liquidated in September 1943, and the Nazis rounded up the last of Vilna’s Jews for deportation, Kovner led a last-gasp escape of 90 Jewish fighters who made their way to the forests outside the city. There, he assembled a band of Jewish partisans known as the Nokmim (the Avengers) that carried out sabotage raids and attacks on Nazis and their local collaborators.

After the Soviets liberated Vilna, Kovner escorted survivors to Palestine. He also hatched a terrible plan to kill six million Germans by poisoning the water supplies of German cities. This plan was abandoned although he and others did attempt to kill German POWs with arsenic. Settling in Israel, he served as an information officer for the Haganah during the 1948 War of Independence and gained fame – and some notoriety – for his angry bulletins calling for “death to the Egyptian invaders” (whom he described as dogs and vipers) as revenge for the Holocaust.

For the rest of his life, Kovner worked on Kibbutz Ein HaHoresh, wrote poetry – he won the Israel Prize for Literature in 1970 – and planned Holocaust memorials. In 1961, he testified at the Eichmann trial. Tormented by memories of the Holocaust, he once commented that for 30 years he had the same dream every night of being chased as his attackers shouted “Raus, raus (out, out)” in German. He died in 1987.

Vitka Kempner-Kovner 1920-2012

The Jewish resistance fighter and leader Vitka Kempner-Kovner was born in 1920 in western Poland. Independent and intrepid, she worked for her living while still a teenager and, drawn in part by the chance to serve in a paramilitary organization, became one of the first females to join Betar, the right-wing Zionist group. She later joined the socialist-Zionist Hashomer Hatzair.

“Refusing to be humiliated” by the Nazis, in 1939 she and her brother escaped occupied Poland. She settled in Vilna where many Zionist youth leaders had gathered. By the time of the Nazi occupation of Lithuania in 1941, these young freedom fighters had gone underground. Using forged papers, Kempner lived outside the Vilna ghetto and helped underground comrades, including the man she would later marry, Abba Kovner, find shelter from the Nazis.

Following the murder of most of Vilna’s Jews in 1941, Kempner and other leaders of the underground decided to come out of hiding, to return to the ghetto, and to embark on a desperate plan of resistance to the Nazis. In 1942, Kempner led the first act of sabotage carried out by the newly formed United Partisans Organization (FPO) when she stole out of the ghetto and used a homemade bomb to blow up a German military train. Despite sporadic individual successes such as this, the underground could not convince Vilna’s mainstream Jewish leaders and the hard-pressed ghetto inhabitants to embark on a general, armed uprising against the Nazis that would inevitably end in defeat.

When the Germans began to liquidate the ghetto, Kempner used her intimate knowledge of the escape routes through the ghetto’s sewerage system to ferry partisans and weapons to forests outside the city. Here she joined combat missions but, despite suffering hunger and malnutrition, refused to join other partisans in seizing food and material from nearby farmers. Women such as Kempner and Rozka Korczak played a significant role in the Jewish partisans, with the group’s leader Kovner often insisting that all missions include at least one woman. In July 1944, Kempner commanded a partisan unit that reached liberated Vilna with the conquering Soviet army.

After the war ended, Kemper joined Kovner in organizing the exodus of Eastern Europe survivors to Palestine and participated in the Nokdim (Revenge) group which carried out reprisal attacks against Germans POWs. Kempner saw these attacks as essential acts of historical justice. However, by 1946, she had relocated to Palestine and decided that the time for revenge had passed. Despite ill health deriving from her war experiences, she played a full part in Kibbutz Ein HaHoresh, married Kovner, had two children, and was a child psychologist. She died in 2012.

J2 STUFF.

We have everything you need to know before you go. Check out our Instagram my_j2adventures for cool updates and interesting tidbits.

The J2 App

available on the App Store & on Google Play.

START PLANNING LET’S EXPLORE.

Whether you have a journey in mind, want to join a featured trip, or simply want to explore, drop us a note. We work really hard to be a loved travel company that delivers amazing and memorable experiences. So please do not be surprised when we say “yes” to every reasonable request you make!