Rabbi Samuel De Medina 1505-1589

Rabbi Samuel ben Moses de Medina was the major Jewish leader in Thessaloniki (Salonika) as that city became home to one of the world’s great Jewish communities. He helped make Salonika a dynamic and, in many ways, fiercely independent center of Sephardi culture and scholarship.

His was a life marked by public achievement and personal tragedy. He was from a prominent rabbinical family that fled persecution in Portugal and Spain and dispersed around the Ottoman Empire. His parents came to Salonika, which in the 16th century was rapidly growing into a key port city with a mainly Jewish population. They died when Samuel was a child. He was raised and, as an adult, financially supported by his elder brother. After his brother died, de Medina was forced to periodically leave Salonika, apparently in search of funds to sustain his dependents, which included two widowed daughters and his grandchildren. The death of his eldest son was another blow, after which de Medina’s spirits and health declined.

Despite these travails, de Medina was a formidable and famously self-confident religious leader. He studied traditional Jewish texts constantly as a young man before establishing a renowned yeshiva (a school of higher Jewish learning) in Salonika. Here, many future rabbinical leaders were schooled in the Spanish system of Talmudic scholarship. He had little interest in the kabbalah and mystical ideas that were becoming powerful in the Sephardi world, nor did he deal deeply with philosophical matters or secular scholarship. Rather, he was accepted, for generations, as the major authority in what is today Turkey, Greece, and the Balkan nations on Jewish religious law (halakha). He inspired and demanded respect. As one rabbi later put it, de Medina was “an expert judge and of encyclopaedic knowledge and one must not deviate an iota from his decisions.” In numerous rabbinical disputes, his views prevailed. Indeed, other rabbis would try to ensure support for their decisions by taking an oath that they had followed the path of Rabbi de Medina. Jews from around the Ottoman Empire would send their religious questions to him. He was decidedly not awed by other eminent rabbis of his time. Indeed, de Medina fiercely rebuked the powerful leaders of Tsfat in the Land of Israel, including the legendary Joseph Caro, for having the temerity to intervene in Salonika’s affairs.

This self-confidence allowed him to be, within his strictly “orthodox” Jewish milieu, an innovator and radical. As later commentators have noted, he was “utterly fearless” in making rulings that accorded with his own judgement but were without precedence in Jewish law. In his day-to-day work as a judge in Salonika’s Jewish law courts he would frequently insist litigants accept a just compromise in their disputes even if it contradicted usual legal standards. He constantly asserted that halakha must reflect contemporary realities and was bold enough to declare that certain opinions found in the Talmud “do not apply in our own time.”

Rabbi de Medina used his standing to create greater cohesion among Salonika’s linguistically, religiously, and economically diverse Jewish populations. Jews had flocked suddenly to Salonika from many parts of the Jewish world and had subsequently formed dozens of largely independent congregations, each following the customs and rulings of their native lands. However, de Medina’s religious and communal judgements found wide acceptance, and he acted assertively to prevent schisms. Despite being a man powerfully attuned to local customs, he worked successfully to make sure that some of Salonika’s customs gradually changed to become in accordance with Spanish Jewish law. He was particularly influential in integrating the “Marranos,” Spanish and Portuguese Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity, into Salonika’s Jewish community. By the time Rabbi de Medina died in 1589, a unique and coherent Jewish culture and community had developed in Salonika.

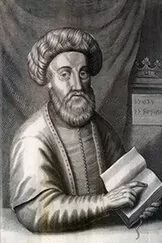

Shabbetai Zevi 1626-1676

The “false messiah” Shabbetai Zevi created one of the greatest disputes in Jewish history. He was born in Smyrna (Izmir), a predominantly Greek-speaking city that is today part of Turkey. His father was a wealthy and pious merchant. Shabbetai received a solid education in Talmud but was drawn to kabbalah and mysticism. He suffered, most scholars believe, from a bipolar disorder. Usually a pleasant, restrained character, in times of manic happiness he was prone to declaring himself the messiah and transgressing Jewish law, for instance by reciting the ineffable name of God. After these manic, messianic episodes, he frequently suffered periods of depression and uncertainty.

Around 1651, he was banished from Smyrna. He eventually based himself in Salonika, whose large Jewish community included many kabbalists. However, the city’s major rabbis were outraged when he publicly “married,” under the wedding huppa, a Torah scroll. Shabbetai, a largely unknown mystic-eccentric was again cast out, spending years wandering in Egypt, Israel, and elsewhere.

But from 1663, countless Jews began to revere Shabbetai. He married a beautiful Jewish prostitute named Sarah, who was famous for her predictions that she was destined to wed the messiah. The key to his new popularity was his disciple and prophet, a brilliant twenty-year-old mystic called Nathan of Gaza. Nathan created and publicized an intricate kabbalist philosophy or theology explaining that Shabbetai was indeed the messiah, and his apparent “sins” were actually part of a mystical tikkun or repair of the world. In 1665, Nathan announced that Shabbetai would soon usher in the messianic age and that, while riding a lion, he would lead the Jews back to Israel.

The reaction was astonishing. Jews in Avignon, France abandoned their homes as they prepared to march with Shabbetai. Others thought they would travel to Israel on clouds. In many countries, respected Jewish leaders signed parchments acknowledging Shabbetai as the messiah. Prayers for Shabbetai “our Lord and King” were recited in synagogues around the world. In Smyrna and elsewhere, rabbis and others who doubted Shabbetai were silenced by threats and by the public tumult. Commentators believe that this outbreak of messianic fervor among Jews reflected a yearning for redemption in the wake of recent massacres in Europe. Isaac Luria and his group of Tsfat mystics had sparked new interest in kabbalah. European Jews were exposed to the messianic ideas of their Christian neighbors and many Christian millenarians were fascinated by Shabbetai.

In 1666, Shabbetai set off to Constantinople (Istanbul), planning to peacefully depose the Ottoman sultan as the first step in the messianic process. He was quickly arrested. At first, Jewish support grew still more passionate as stories of the Messiah’s steadfastness in prison spread throughout Europe, the Mediterranean, and North Africa. But in September, the sultan offered Shabbetai a choice: conversion to Islam or death. He chose the former. He was released and lived the rest of his life as a Muslim while practicing Jewish rituals secretly. He continued to claim to be the messiah.

Shabbetai’s conversion disillusioned most of his followers who generally slipped back into mainstream Judaism. Salonika, however, remained a stronghold for his loyalists. In Turkey in 1674, he married the daughter of a respected Salonika rabbi. When he died in 1676, she and hundreds of his staunchest followers returned to Salonika. In imitation of their messiah, they publicly proclaimed themselves Muslims while secretly practising Judaism. This community, known as the Donmeh, was active in Salonika for hundreds of years, and influential elsewhere.

Shabbetai’s spiritual heirs include another, even wilder, Jewish messianic movement. Jacob Frank, who had spent time among the Donmeh in Salonika, claimed to be a reincarnation of Shabbetai. In the 18th century he launched his own messianic movement in Eastern Europe, complete with sacred orgies and ideas of “purification through transgression.” It is said to have had 500,000 followers.

Roza Eskenazi mid 1890s-1980

Roza Eskenazi was the “Billie Holliday of the Greek blues.” She was the queen of rebetiko, a musical style hugely popular among Greek’s urban poor with its songs of love, joy, and sorrow. Born Sarah Skinazi, she was part of an impoverished Sephardi family from Constantinople (Istanbul) that moved, when she was young, to the booming Jewish city of Thessaloniki (Salonika) in Greece. Her father and mother were somewhat itinerant, working as rag traders, as money changers, as a maid, and as mill workers. Her birthdate is uncertain, in part because she was prone to shaving years off her actual age. Roza did not attend school but was literate and multilingual, singing in multiple languages including Greek, Turkish, Arabic, Armenian, Italian, Ladino, and Yiddish.

Determined to be a performer from a young age, she encountered resistance from her parents. Performing was, particularly for young women, less than respectable, and Roza was beaten when they discovered that she had danced at a local theater. Around 1910, the teenage Roza met a wealthy local man. His parents, considering Roza of questionable morals, disapproved of the match. The couple eloped but her husband soon died. Sarah changed her name to Roza, placed their young son in a children’s home (they would be reconciled many years later), and spent almost two decades as a little-known singer and dancer in nightclubs and taverns around Greece.

In 1929, Roza was at last “discovered” by a prominent composer and record label boss. Her first recordings were a marked success and helped bring rebetiko and other forms of Greek folk music into the mainstream. She would record over 500 songs in the following decade. Her music, and rebetiko more generally, was popular throughout the Mediterranean and Balkans. She toured widely, including to her native Turkey, despite the poor relations between that country and Greece. With connections to many cultures, she used to say music was her nationality.

She wrote the lyrics and music to some of her songs but was best known for her voice. It has been described as simultaneously hard and yearning, “a mingling of desire, infatuation, and pain.” She was perhaps the most popular and well-remunerated Greek singer of her time, although a fondness for expensive jewelry strained her finances. She had other troubles. Her second husband, a famous actor, drank himself to death. Like many rebetiko singers, she often sang of profane subjects and her song “When You Take Heroin” was banned by the Greek dictator of the 1930s, Ioannis Metaxas.

It would seem that her Jewishness was not widely known, and she continued to perform at the Athens nightclub she owned even after the German army occupied Greece in 1941. She was protected by a false baptismal certificate and a real German officer who was her lover. During this time, she hid Greek resistance fighters, British soldiers, and Jews, including her own family. In 1943, she was arrested, apparently because her Jewishness had been discovered. Her German paramour managed to have her released and she spent the rest of the war years in hiding.

After the war, Eskenazi spent extended periods in the US, singing to the large Greek and Turkish diasporas there. In 1959, she returned to Athens to be with her new partner, a Greek police officer many years her junior. They would remain together for the rest of her life. Rebetiko music and Roza had both fallen out of fashion by then. She continued to perform in nightclubs and on television until 1977 (when she was probably 80-plus years old), but when she died in 1980, the public had largely forgotten her. Nonetheless, musicians and musicologists have continued to rediscover the power of her voice, and the earthy authenticity of the music she made. In 2011, a documentary on her life, named My Sweet Canary after one of her most popular songs, was released.

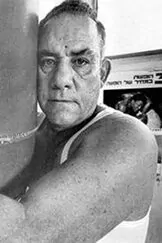

Salamo Arouch 1923-2009

The boxer Salamo Arouch survived Auschwitz through unquenchable determination and the force of his fists. He was born in Thessaloniki (Salonika) and like many of his Sephardi family, worked as a stevedore on the city’s docks. Tutored in boxing by his father, from the age of 14 he built up an undefeated record, becoming the middleweight (amateur) champion of Greece and then of all the Balkans. His ambition to fight in the Olympics was ended by World War II, during which he served with the Greek army that was routed by the invading Germans.

In 1943, he, his family, and over 40,000 Jews from Salonika were deported to Auschwitz. His mother and sister were gassed immediately upon arrival. But the camp commandant, on the lookout for entertainment, asked whether any of the male newcomers were boxers. Arouch raised his hand. A circle was drawn in the dirt, and the frightened, tired Arouch was ordered to fight a Jewish opponent. After he defeated him, the five-foot-six Arouch then knocked out a six-foot Czech.

Arouch had passed his audition and was selected to participate in Auschwitz’s version of gladiatorial combat or a human cockfight. He was provided with lighter work duties and better rations and, twice a week, with new opponents. The camp guards would drink, yell, and bet on the outcome, the bouts finishing when a man was knocked out or the guards grew bored. Roma inmates were sometimes ordered to juggle, to keep the guards amused.

Arouch quickly realized that losing a fight could mean losing his life. The losers of the bouts, he said, would be badly weakened, “and the Nazis shot the weak.” Twice, while suffering from dysentery, Arouch only just escaped with draws. On another occasion, a heavier, formerly professional boxer named Klaus Silber almost defeated him. Arouch survived. After the bout, Silber disappeared. By his tally, Arouch fought 208 fights in Auschwitz without defeat.

Arouch’s will to live did not falter even after his ill father was executed in Auschwitz and his brother was shot for refusing to take gold from the teeth of those gassed. In 1945, he was transferred to Bergen-Belsen where he worked as a slave laborer. After the camp was liberated by the Allies, he traveled through Europe hoping to find surviving relatives. Instead, he met 17-year-old Marta Yechiel, the sole survivor of her Salonika family. They married and moved to Israel, and Arouch fought in the country’s 1948 War of Independence. He also briefly resumed his boxing career before developing a successful shipping and moving business.

In 1988, he returned to Auschwitz to serve as an adviser to a film based on his life, Triumph of the Spirit, starring Willem Dafoe. It was the first film to be shot at the camp. He found the return a traumatic experience but explained that what had kept him alive during his original time in the camp was a “burning determination to someday tell the world what I saw at Auschwitz.” Salamo Arouch suffered a stroke in 1994 and died in 2009, survived by his wife and four adult children.

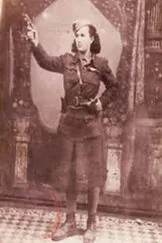

Sara Fortis born 1927

Known as “Captain Sarika,” the teenage Sara Fortis was the leader of an all-female unit of Greek resistance fighters during World War II. Born Sarika Yehoshua, her father died when she was just two months old. Nonetheless, she enjoyed a happy childhood, free from anti-Semitism, on the island of Euboea. Her family observed some Jewish rituals while identifying strongly as Greek patriots. Indeed, her uncle Mordechai Frizis was a Greek military hero, a high-ranking officer who died helping the Greek army repel the Italian invasion of 1940.

However, a year later the Germans and their allies occupied Greece. For a period, the family continued to live in their village, presenting themselves as Christians, with the 14-year-old Sara acting as a nurse to wounded Greek fighters. But in 1943, as news of German atrocities spread, Sara and her mother fled to the island’s isolated mountains. A 12-hour donkey ride brought them to a village where Sara initially worked as a teacher. As the Nazi threat grew nearer, Sara’s mother hid with a local family while Sara became an andarte (resistance fighter). The Greek partisans fighting the Nazis were probably the most fierce and successful in all of Europe. Many women were involved in nursing and other duties. Most unusually, Sara insisted upon a combat role and was also granted permission to form a unit of female fighters. Given the conservative attitudes toward gender roles in local villages, recruitment was no simple matter, but she eventually led a team of 12 (non-Jewish) young women. After a month of training, the members were no longer giggling nervously when handling firearms but were ready to fight.

Their first mission involved throwing Molotov cocktails at German troops and drawing them out of to a place of vulnerability where they were then attacked by other partisans. The success of this attack impressed previously skeptical male resistance leaders. Seventeen-year-old Fortis went on to lead a series of attacks on German supplies and troops, and the killing of collaborators. Her unit often used their gender and age as a tactic, portraying themselves during missions as young teenage girls innocently playing. Although many believe that her unit, because they were female, did not receive the recognition they deserved, “Captain Sarika” gained a formidable reputation among the Germans. They ordered a Greek collaborator to kill her. In a case of mistaken identity, he instead sadistically murdered a female Jewish teacher. Fortis subsequently hunted down and killed the collaborator.

While her Jewishness was not an issue with the Greek partisans, gender was. Among her other duties, Sara rigorously guarded against any sexual connection between her troops and the male resistance fighters they served alongside, as this could be devastating for the young women’s future. Despite her fears, her soldiers were welcomed back to their villages with pride after the German withdrawal in 1944. However, the disunity between the different partisan organizations presented a new danger. Royalist right-wing partisans took charge of the new government, executing thousands of partisans connected with leftist groups in a prelude to the civil war which would roil the country for years. Sara Fortis was imprisoned. She was eventually released and emigrated to Israel. She married, and her son was a decorated fighter in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. She was unhurt when her house was destroyed by a Scud missile in 1991 during the Gulf War. Sara Fortis still lives, well into her 90s, in Israel.

J2 STUFF.

We have everything you need to know before you go. Check out our Instagram my_j2adventures for cool updates and interesting tidbits.

The J2 App

available on the App Store & on Google Play.

START PLANNING LET’S EXPLORE.

Whether you have a journey in mind, want to join a featured trip, or simply want to explore, drop us a note. We work really hard to be a loved travel company that delivers amazing and memorable experiences. So please do not be surprised when we say “yes” to every reasonable request you make!